George "Where There's a Way" Will is getting a few pats on the back for declaring Sarah Palin 2 Dumb 2 Run. But in today's column he proves that behind the veneer of vocabulary and erudition, he's no better able to distinguish between excrement and Shinola.

First he makes a statement more obnoxious and offensive than anything I recall Palin uttering: "in other times, Jews or railroad owners or hard-money advocates; today, the villain is "Wall Street greed," which is contrasted with the supposed sobriety of "Main Street."

Then he pulls this buried lede/thesis out of his sphincter, the common denominator in the idiotic conservative analyses of the crash:

Suppose there had never been implicit government backing of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Better yet, suppose those two had never existed -- there was homeownership before them, just not at a level that the government thought proper. Absent Fannie and Freddie -- absent government manipulation of the housing market -- would there have developed the excessive diversion of capital into the housing stock?

Now there's a strong case to be made regarding this country's culture of debt. And Fannie and Freddie were big problems in their own right. But the latter Did. Not. Create. This. Crisis. Not only has George F. dispensed with causation, he doesn't even bother with correlation. Behold:

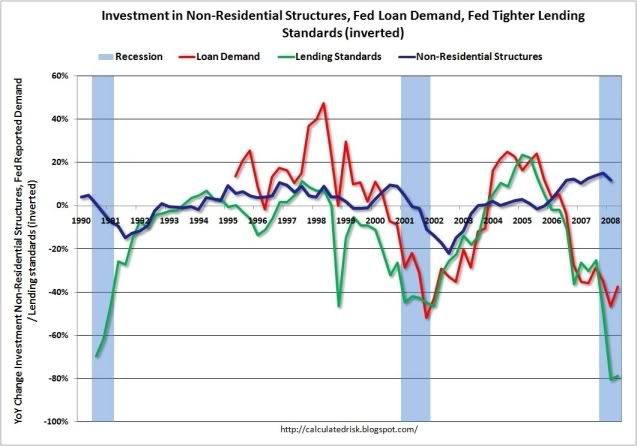

That green line screaming up represents lending standards falling down (this chart doesn't show it specifically, but there was a corresponding increase in supply/demand of residential mortgage loans see here). This had absofrickinglutely nothing to do with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

What happened in 2001-2002 to touch off the lending spree? Ask this little libertarian leprechaun.

The mortgage mania was a manifestation of the extremely profitable arbitrage opportunities between the low Fed rates and mortgage interest rates - particularly obnoxiously high subprime rates. Greenspan planned it that way, as a means of avoiding the fallout from the previous bubble.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac decreased their dalliance in subprime lending until 2006, when as you can see was on the downward swing of demand. Even then they represented a fraction of the market. And they didn't jump back in because of a librul mandate to lend to the underclass; they did it because they were getting their ass kicked in market share and wanted a piece of the action.

How conservatives got the reputation of being hard-nosed economic realists is beyond me.

|

Topics:

|

|

Discussing:

- Trump wouldn't call Minnesota governor after Democrat was slain but now blames him for raised flags (1 reply)

- Denso unveils pavillion in Maryville (1 reply)

- Ex-CDC Directors are worried and say it well (4 replies)

- Jobs numbers worst since 2020 pandemic (1 reply)

- Tennessee training MAGAs of tomorrow (4 replies)

- Knoxville, "the underrated Tennessee destination" (1 reply)

- Country protectors assigned park maintenance tasks (1 reply)

- City of Knoxville election day, Aug. 26, 2025 (1 reply)

- Proposals sought for Fall 2025 Knoxville SOUP dinner (1 reply)

- Is the Knoxville Civic Auditorium and Coliseum ugly? (1 reply)

- President says: no mail-in voting and no voting machines (2 replies)

- Will the sandwich thrower be pardoned? (3 replies)

TN Progressive

- WATCH THIS SPACE. (Left Wing Cracker)

- Report on Blount County, TN, No Kings event (BlountViews)

- America As It Is Right Now (RoaneViews)

- A friend sent this: From Captain McElwee's Tall Tales of Roane County (RoaneViews)

- The Meidas Touch (RoaneViews)

- Massive Security Breach Analysis (RoaneViews)

- (Whitescreek Journal)

- Lee's Fried Chicken in Alcoa closed (BlountViews)

- Alcoa, Hall Rd. Corridor Study meeting, July 30, 2024 (BlountViews)

- My choices in the August election (Left Wing Cracker)

- July 4, 2024 - aka The Twilight Zone (Joe Powell)

- Chef steals food to serve at restaurant? (BlountViews)

TN Politics

- Trump ties autism to Tylenol use in pregnancy despite inconclusive scientific evidence (TN Lookout)

- One Big Beautiful Bill Act food assistance cuts come with hefty price tag for Tennessee taxpayers (TN Lookout)

- EPA terminates $156M solar power program for low-income Tennesseans (TN Lookout)

- National Guard presence in Memphis demands collaboration over partisanship (TN Lookout)

- Trump headlines Arizona memorial service for Charlie Kirk at packed stadium (TN Lookout)

- Chance of government shutdown rises as US Senate fails to advance spending bill (TN Lookout)

Knox TN Today

- Andrew Creswell: Frequent fights (Knox TN Today)

- Big Al and Heather DeBord’s lifelong bond (Knox TN Today)

- Maryville College named to PTK honor roll for transfer student success (Knox TN Today)

- Bull Run Fossell Fuel Plant has a future (Knox TN Today)

- Safety deposit boxes: Benefits and considerations (Knox TN Today)

- Island Home field trip; Hillcrest golf tournament ahead (Knox TN Today)

- HEADLINES: World to local Tune It Up Tuesday, Jackie’s Dream and more (Knox TN Today)

- Blessing of the animals at Church of the Good Shepherd (Knox TN Today)

- We are Inskip block party is Saturday (Knox TN Today)

- Build a Better World Conference is Saturday (Knox TN Today)

- Beware: Something is going on at Mississippi State (Knox TN Today)

- KPD horses are named (Knox TN Today)

Local TV News

- Lady Vol great Kara Lawson to lead Team USA at 2028 Olympics (WATE)

- VIDEO: 4-year-old Knoxville golfer sinks hole in one (WATE)

- Tennessee announces new work requirements for adults receiving SNAP benefits (WATE)

- Knox County Regional Forensic Center to become medical examiner for Blount County (WATE)

- 'Do the right thing': Family wants justice after fatal hit-and-run in Madisonville (WATE)

- Retired Knoxville firefighter battling for Social Security disability benefits after career-ending injury (WATE)

News Sentinel

State News

- UAW taking temperature for strike at Volkswagen Chattanooga - Chattanooga Times Free Press (Times Free Press)

- Chattanooga bluegrass festival helps some businesses, hinders others - Chattanooga Times Free Press (Times Free Press)

- Vols face vastly improved Bulldogs; Heupel praises Boo Carter - Chattanooga Times Free Press (Times Free Press)

- Opinion: The undue influence of Moms for Liberty - Chattanooga Times Free Press (Times Free Press)

Wire Reports

- Trump urges pregnant women to avoid Tylenol over unproven autism risk - Al Jazeera (US News)

- Argentina’s Javier Milei to meet Donald Trump for talks on US financial lifeline - Financial Times (Business)

- Business leaders including Jensen Huang, Sam Altman, and Reed Hastings, react to Trump's H-1B visa fee - Business Insider (US News)

- Exclusive: China ask brokers to pause real-world asset business in Hong Kong, sources say - Reuters (Business)

- Federal judge orders Trump to restore $500 million in frozen UCLA medical research grants - Los Angeles Times (US News)

- Takeaways from Kamala Harris’ first interview about her new book, ‘107 Days’ - CNN (US News)

- Man suspected of shooting at ABC affiliate had note to ‘do the next scary thing,’ prosecutors say - The Hill (US News)

- Why some Bay Area residents woke up moments before Monday morning's earthquake - San Francisco Chronicle (US News)

- Trump Signs Order Targeting Antifa Movement - The New York Times (US News)

- Google seeks to avoid ad tech breakup as antitrust trial begins - Reuters (Business)

- China Floods the World With Cheap Exports After Trump’s Tariffs - Bloomberg (Business)

- Judge says construction of large offshore wind farm near Rhode Island can resume - WBUR (Business)

- S&P 500 Gain & Losses Today: Oracle, Nvidia Shares Advance; Kenvue Stock Slips - Investopedia (Business)

- Man charged with aiming laser pointer at Trump's helicopter - NBC News (US News)

- Building A $100,000 Dividend Portfolio: Maximizing SCHD's Income With September's Top High-Yield Stocks - Seeking Alpha (Business)

Local Media

Lost Medicaid Funding

Search and Archives

TN Progressive

Nearby:

- Blount Dems

- Herston TN Family Law

- Inside of Knoxville

- Instapundit

- Jack Lail

- Jim Stovall

- Knox Dems

- MoxCarm Blue Streak

- Outdoor Knoxville

- Pittman Properties

- Reality Me

- Stop Alcoa Parkway

Beyond:

- Nashville Scene

- Nashville Post

- Smart City Memphis

- TN Dems

- TN Journal

- TN Lookout

- Bob Stepno

- Facing South

excrement and Shinola

Out of curiosity, what is the difference between excrement and Shinola?

About four percentage

About four percentage points.

Shinola went on the top of

Shinola went on the top of your shoes.

Visit us at

The Home

:-)

Aren't you being redundant?

It's the bowtie.

"When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro."

Hunter S. Thompson

What a bunch of

What a bunch of self-adulatory bul*shit.

Your critique of this statement reveals your utter lack of historic context, and your also utter lack of understanding of the older politics of demonization, an older politic you mimic without realizing it, apparently.

Nobody, not you, not George Will, is suggesting that the sole cause of the present credit nuttiness is the Freddie and Fannie nexus.

You should at least try to address the question you seem to to be trying to avoid debunking before you dismiss Will as an "idiot," which is itself idiotic.

You can surely do better than this.

older politics of

older politics of demonization

Right. Will claims that calling Wall Street greedy is akin to blaming economic crisis on Jews.

Do you not see the problem with that?

George Will, is suggesting that the sole cause of the present credit nuttiness is the Freddie and Fannie nexus

Oh yeah. His argument is so much more nuanced. The "democratization of credit" plus the "entitlement mentality fostered by the welfare state plus "government manipulation of the housing market."

Note that he doesn't provide any evidence that any of these had anything to do with the rapid loosening of lending standards beginning in 2001.

My evidence is that the loosening corresponds perfectly with the Fed's rate cuts. And don't take my word for it. Alan Greenspan said explicitly at the time that he was trying to boost the housing market with cheap credit.

Re-read Will!

You say two things here that lead me away from believing that you're just mendacious, and towards the conclusion that you're just uncomprehending.

Yeah. Right. That's exactly what he said. Maybe you should read with a little more care. You've totally missed his point, which, now that I think about it is probably fine since he's a bleeping idiot anyway.

Maybe that's because that's not what Will's column is about, Sven. This column isn't about locating the causes of the present crisis. It's about the logical fallacies potential in populist critiques of phenomena that are, yes, way more nuanced than either you or your mirror-image blame-mongers on the right would like to admit.

And Will is far from idiotic. He has made useful observations in this column, as opposed to your reductionist attempts to peg the whole mess to the Fed's making credit more readily available to the housing market.

You should at least try to understand the people you oppose, and dispense with the eighth-grade name-calling crap. You've got to have penetrating analysis to offer here; I've seen glimmers of it before. Why not contribute to some actual understanding, instead of wallowing in this solipsistic progressive muddle?

Will, like other

Will, like other conservative commentators, continues to claim that the problem was caused by easy credit and unqualified borrowers and the government.

Of course, he's just doing that to try to divert attention from the actual problem, which was securitizing anything and everything and turning it over to Wall Street, and then allowing banks and other institutions to invest into these securities using debt.

As long as home prices kept climbing, investors could keep up with payments on the money they had borrowed to buy those securities, once the home values dropped though, so did the dividends, and thus, the ability to keep up with the loan payments. On a massive, massive scale.

Quite close to what happened with what happened in 1929, with so many stocks being bought with borrowed money.

Conservatives don't want to admit that the financial euphoria of private industry led to this disaster. But that's what happened.

Here's a paper by a

Here's a paper by a Princeton economist that argues, persuasively IMO, that the market could have easily weathered the subprime storm - it amounted to about 2-3% of the DOW, and we routinely experience that kind of swing.

It was all the crazy, unregulated "innovation" that was built on top of the mortgage market that amplified the financial damage and, even more importantly, destroyed trust among the players.

It was all the crazy,

It was all the crazy, unregulated "innovation" that was built on top of the mortgage market that amplified the financial damage and, even more importantly, destroyed trust among the players.

The "innovations" are also why the business leaders will not back the conservatives call for providing insurance instead of a "bailout."

Insurance won't help since nobody even wants to try trading the toxic securities in the first place. Wall Street knows this, and that's why Paulson pushed for the plan that he did.

Congressional conservatives are so disconnected that even their "free enterprise" and "market" solutions to the problem are being completely ignored by financiers and capitalists on Wall Street.

Think about that a minute, and let it sink in. You are in fact witnessing the demise of the neocon philosophy of economics.

I have a feeling that in the next few elections Wall Street will remember who helped them out, along with the US economy, when the Republican fundraisers start calling. That is the big story.

Yep!

"You are in fact witnessing the demise of the neocon philosophy of economics".

And only about eight years too late.

Neocon Economics 101:

Loot, loot, loot. Then blame Democrats.

I was just watching the History Channel. They said that Yetis were Jewish. Offered Esau as an example.

It's nutz out there I tell ya.

heh

Note the sharp decline around 1999.

Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act

End of story.

The Dems opposed it, the Republican majority pushed it, and that Right Wing lapdog, Billary Clinton failed to veto it.

I apologize for the length of this but the link at Thomas changes with updates etc.

This is Sen. Byron Dorgan(D) predicting everything we're going through today back in '99.

Here is Senator Dorgan's speech. Amazing.

From the congressional Record dated 05/06/99.

Mr. DORGAN. Mr. President, we are debating a piece of legislation in the Senate that is called the Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999.

I come today with the confession I am probably hopelessly old fashioned on this issue. For those who have a vision of re-landscaping the financial system in this country with different parts operating with each other in different ways and saying that represents modernization, then I am just hopelessly old fashioned, and there is probably nothing that can be said or done that will march me towards the future.

I want to sound a warning call today about this legislation. I think this legislation is just fundamentally terrible. I hear all these words about the indus try remaking itself--banks, security firms and insurance companies, and that we'd better catch up and put a fence around where they are or at least build a pasture in the vicinity of where they are grazing. What a terrible idea.

What is it that sparks this need to modernize our financial system? And what does modernization mean? This chart shows bank mergers in 1998, in just 1 year, last year, the top 10 bank mergers. We have discovered all these corporations have fallen in love and decided to get married. Citicorp, with an insurance company--that is a big one--$698 billion in combined assets; NationsBank--BankAmerica, $570 million; and the list goes on. This is a massive concentration through mergers.

Is it good for the consumers? I don't think so. Better service, lower prices, lower fees? I don't think so. Bigger profits? You bet.

What about the banking industry concentration? The chart shows the number of banks with 25 percent of the domestic deposits. In 1984, 42 of the biggest banks had 25 percent of the biggest deposits. Now only six banks have the biggest deposits. That is a massive concentration.

I didn't bring the chart out about profits, but it will show --this is an industry that says it needs to be modernized--banks have record-breaking profits, security firms have very healthy profits, and most insurance companies are doing just fine. Why is there a need to modernize them?

So we must ask the question, what about the customer? What impact on the economy will all of this so-called modernization have?

It is interesting to me that the bill brought to the floor that says, ``Let's modernize this,'' is a piece of legislation that doesn't do anything about a couple of areas which I think pose very serious problems. I want to mention a couple of these problems because I want to offer a couple of amendments on them.

I begin by reading an article that appeared in the Wall Street Journal, November 16, 1998. This is a harbinger of things to come, just as something I will read that happened in 1994 is a harbinger of things to come, especially as we move in this direction of modernization.

It was Aug. 21, a sultry Friday, and nearly half the partners at Long-Term Capital Management LP [that's LTCM, a company] were out of the office. Outside the fund's glass-and-granite headquarters, a fountain languidly streamed over a copper osprey clawing its prey.

Inside, the associates logged on to their computers and saw something deeply disturbing: U.S. Treasurys were skyrocketing, throwing their relationship to other securities out of whack. The Dow Jones Industrial Average was swooning--by noon, down 283 points. The European bond market was in shambles. LTCM's biggest bets were blowing up, and no one could do anything about it.

This was a private hedge funding.

By 11 a.m., the [hedge] fund had lost $150 million in a wager on the prices of two telecommunications stocks involved in a takeover. Then, a single bet tied to the U.S. bond market lost $100 million [by the same company]. Another $100 million evaporated in a similar trade in Britain. By day's end, LTCM [this hedge fund in20New York] had hemorrhaged half a billion dollars. Its equity had sunk to $3.1 billion--down a third for the year.

This company had made bets over $1 trillion.

Now, what happened? They lost their silk shirts. But of course, they were saved because a Federal Reserve Board official decided we can't lose a hedge fund like this; it would be catastrophic to the marketplace. So on Sunday night they convened a meeting with an official of the Federal Reserve Board, and a group of banks came in as a result of that meeting and used bank funds to shore up a private hedge fund that was capitalized in the Caymen Islands for the purpose, I assume, of avoiding taxes. Bets of over $1 trillion in hedges--they could have set up a casino in their lobby, in my judgment, the way they were doing business. But they got bailed out.

This was massive exposure. The exposure on the hedge fund was such that the failure of the hedge fund would have had a significant impact on the market.

And so we modernize our banking system. This is unregulated. This isn't a bank; it is an unregulated hedge fund, except the banks have massive quantities of money in the hedge fund now in order to bail it out.

What does modernization say about this? Nothing, nothing. It says let's pretend this doesn't exist, this isn't a problem, let's not deal with it.

So we will modernize our financial institutions and we will say about this problem--nothing? Don't worry about it?

I find it fascinating that about 70 years ago in this country we had examples of institutions the futures of which rested on not just safety and soundness of the institutions themselves but the perception of safety and soundness, that is, banks. Those institutions, the future success and stability of which is only guaranteed by the perception that they are safe and sound, were allowed, 70 years ago, to combine with other kinds of risk enterprises--notably securities underwriting and some other activities--and that was going to be all right. That was back in the Roaring Twenties when we had this go-go economy and the stock market was shooting up like a Roman candle and banks got involved in securities and all of a sudden everybody was doing well and everybody was making massive amounts of money and the country was delirious about it.

Then the house of cards started to fall. As investigations began and bank failures occurred and bank holidays were declared, from that rubble came a description of a future that would separate banking institutions from inherently risky enterprises. A piece of legislation called the Glass-Steagall Act was written, saying maybe we should learn from this, that we should not fuse inherently risky enterprises with institutions whose perception of safety and soundness is the only thing that can guarantee their future success. So we created circumstances that prevented certain institutions like banks from being involved in other activities such as securities underwriting.

Over the years that has all changed. Banks have said, because everybody else has decided they want to intrude into our business--and that is right, a whole lot of folks now set themselves up in a lobby someplace and say we are appearing to be like a bank or want to behave like a bank--the banks say if that is the case, we want to get into their business. So now we have the kind of initiative here in the Congress that says: Let's forget the lessons of the past; let's believe the 1920s did not happen; let's not worry about Glass-Steagall. In fact, let's repeal Glass-Steagall; let's decide we can merge once again or fuse together banking enterprises and more risky enterprises, and we can go down the road just as happy as clams and everything will be just great. And of course it will not.

I mentioned hedge funds--talk about risk. How about derivatives? Incidentally, those who vote for this bill will remember this at some point in the future when we have the next catastrophic event that goes with the risks in derivatives. Fortune magazine wrote an article, ``The Risk That Won't Go Away; Financial Derivatives Are Tightening Their Grip on the World Economy and No One Knows How to Control Them.'' Somewhere around $70- to $80 trillion in derivatives.

I wrote an article in 1994 for the Washington Monthly magazine and derivatives at that point were $35 trillion. You know something, today in this country banks are trading derivatives on their own proprietary accounts. They could just as well put a roulette wheel in the lobby. They could just as well call it a casino. Banks ought not be trading derivatives on their proprietary accounts. I have an amendment to prohibit that. I don't suppose it would get more than a handful of votes, but I intend to offer it.

Is it part of financial modernization to say this sort of nonsense ought to stop; that banks ought not be able to trade derivatives on their own proprietary accounts because that is inherently gambling? It does not fit with what we know to be the20fundamental nature of banking and the requirement of the perception of safety and soundness of these institutions. Does anybody here think this makes any sense, that we have banks involved in derivatives, trading on their own proprietary accounts? Does anybody think it makes any sense to have hedge funds out there with trillions of dollars of derivatives, losing billions of dollars and then being bailed out by a Federal Reserve-led bailout because their failure would be so catastrophic to the rest of the market that we cannot allow them to fail?

And as banks get bigger, of course, we also have another doctrine. The doctrine in banking at the Federal Reserve Board is called, ``too big to fail.'' Remember that term, ``too big to fail.'' It means at a certain level, banks get too big to fail. They cannot be allowed to fail because the consequence on the economy is catastrophic and therefore these banks are too big to fail. Virtually every single merger you read about in the newspapers these days means we simply have more banks that are too big to fail. That is no-fault capitalism; too big to fail. Does anybody care about that? Does the Fed? Apparently not.

Of course the Fed has an inherent conflict of interest. I think, if the Congress were thinking very clearly about the Federal

Reserve Board, they would decide immediately that the Federal Reserve Board is not the locus of supervision of banks. The Federal Reserve Board is in charge of monetary policy. It is fundamentally a conflict of interest to be listening to the Fed about what is good for banks when they are involved in running the monetary policy of this country. If the Federal Reserve Board were, in my judgment, doing what it ought to be doing, it would be leading the charge, saying we need to regulate risky hedge funds because banks are involved in substantial risk on these hedge funds. Apparently hedge funds have become too big to fail. Then there needs to be some regulation.

The Fed, if it were thinking, would say we need to deal with derivatives, and that bank trading on proprietary accounts in derivatives is absurd and ought not happen. Some will remember in 1994 the collapse in the derivative area. You might remember the stories. ``Piper's Managers' Losses May Total $700 Million.'' ``Corporation After Corporation Had to Write Off Huge Losses Because They Were Involved in the Casino Game on Derivatives.'' ``Bankers Trust Thrives on Pitching Derivatives But Climate Is Shifting.'' ``Losses By P&G May Clinch Plan to Change.''

The point is, we have massive amounts of risk in all of these areas. The bill brought to the floor today does nothing to address these risks, nothing at all, but goes ahead and creates new risks by saying we will fuse and merge the opportunities for inherently risky economic activity to be combined with banking which requires the perception of safety and soundness.

We have all these folks here who know a lot more about this than I do, I must admit, who say: Except we are creating firewalls. We have subsidiaries, we have affiliates, we have firewalls. They have everything except common sense; everything, apparently, except a primer on history. I just wish, before people would vote for this bill, they would be forced to read just a bit of the financial history of this country to understand how consequential this decision is going to be.

I, obviously, am in a minority here. We have people who dressed in their best suits and they just think this is the greatest piece of legislation that has ever been given to Congress. We have choruses of folks standing outside this Chamber who spent their lifetimes working to get this done, to say: Would you just forget all that nonsense back in the 1930s about bank failures and Glass-Steagall and the requirement to separate risk from banking enterprises; just forget all that. Time has moved on. Let's understand that. Change with the times.

We have folks outside who have worked on this very hard and who very much want this to happen. We have a lot of folks in here who are very compliant to say: Absolutely, let me be the lead singer. And here we are. We have this bill, which I will bet, in 5, 10, 15 years from now, we will be back thinking of this bill like we thought of the bill passed in the late 1970s and early 1980s, in which this Congress unhitched the savings and loans so some sleepy little Texas institution could gather brokered deposits from all around America and, like a giant rocket, become a huge enterprise. And guess what. With all the speculation in the S&Ls and brokered deposits and all the things that went with it that this Congress allowed, what did it cost the American taxpayer to bail out that bunch of failures? What did it cost? Hundreds of billions of dollars. I will bet one day somebody is going to look back at this and they are going to say: How on Earth could we have thought it made sense to allow the banking industry to concentrate, through merger and acquisition, to become bigger and bigger and bigger; far more firms in the category of too big to fail? How did we think that was going to help this country? Then to decide we shall fuse it with inherently risky enterprises, how did we think that was going to avoid the lessons of the past ?

Then the one question that bothers me, I guess, is--I understand what is in this for banks. I understand what is in it for the security firms. I understand what is in it for all the enterprises. What is in this for the American people? What is in it for the American people? Higher charges, higher fees? Do you know that some banks these days are charging people to see their money? We know that because we pay fees, obviously, to access our money at bank machines. But credit card companies, most of them through banks, are charging people who pay their bills on time because you cannot make money off somebody who wants to pay their bill every month.

If you have a credit card balance--incidentally, you need a credit card these days, because it is pretty hard to do business in cash in some places. You know with all the bills, everybody wants to use credit cards. Many businesses want you to use credit cards. So you use credit cards, then you pay off the entire balance at the end of every month because you don't want to pay the interest. Some companies have decided you should be penalized for paying off your whole balance. Isn't that interesting? You talk about turning logic on its head, suggesting we don't make money on people who pay off their credit card balance every month, so let us decide that our approach to banking is to say those who pay their credit card bill off every month shall be penalized.

Turning logic on its head? I think so. As I said when I started, I am likely to be branded as hopelessly old fashioned on these issues, and I accept that. I suspect that some day in some way others will scratch their heads and say, ``I wish we had been a bit more old fashioned in the way we assessed risk and the way we read history and the way we evaluated what would have made sense going forward in modernizing our financial institutions.''

Oh, there is a way to modernize them all right, but it is not to be a parrot and say because=2 0the industry has moved in this direction, we must now move in this direction and catch them and circle them to say it is fine that you are here now. That is not the appropriate way to address the fundamental challenges we have in the financial services industry.

I am not anti-bank, anti-security or anti-insurance. All of them play a constructive role and important role in this country. But this country will be better served with aggressive antitrust enforcement, with, in my judgment, fewer mergers, with fewer companies moving in to the ``too big to fail'' category of the Federal Reserve Board, with less concentration.

This country will be better served if we have tighter controls, not firewalls that allow these companies to come together and do inherently risky things adjacent to banking enterprises, but to decide the lessons of the 1930s are indelible transcendental lessons we ought to learn and ought to remember.

Mr. President, I have more to say, but I understand my time is about to expire.

Source:

(link...)

Does anyone know why the couldn't have given us the money?

What would happen if they gave every adult in America an equal share of the 700 billion dollars? I'm no economist and horrible with numbers, but I have heard this idea passed around lately among the commoners.

Probably not a lot, because

Probably not a lot, because it would be spread too thin.

Consider an analogy -- you go to McDonalds and get a single pack of ketchup. That's enough to cover one small order of fries.

But if you got five super-size orders of fries, that would be enough to add just a little tiny drop of ketchup to each fry -- probably so small you wouldn't taste it at all.

Now, that's not a 100% fair analogy, because if every American, man woman and child, got an equal share of the $7000 billion, that's very roughly $2000 apiece. While to most Americans that's a decent chunk of change, very few people would consider it life changing. You'd pay off a credit card, take a nice vacation, buy a new computer, etc. The economic benefits would be very widely spread out. It would still be noticeable, but throughout the entire economy, including sectors that aren't hurting.

In short, for this to have a real effect, it has to be concentrated in a specific segment.

What would happen if they

What would happen if they gave every adult in America an equal share of the 700 billion dollars? I'm no economist and horrible with numbers, but I have heard this idea passed around lately among the commoners.

I think the $700 billion is meant more as a message. Like foreign aid.

The amount of foreign aid never has anything to do with the country's needs as it is a measurement of the strength of the country's alliance with us.

If the Treasury had offered $200 billion, markets would have said the U.S. isn't serious. If Treasury had offered a trillion, the markets would have said the Treasury is crazy. $700 billion. Not too cold, not too hot. Just right. As far as the message goes, that is.

They said the Asian markets this morning were discounting the Senate vote, because they feel like it doesn't deal with the actual problems that got us here. They're right. But Bush had to do something before November to minimize the damage to the Republican Party. If he hadn't, the Republican Party's very existence would probably have been in question.

Yeah. Right. That's exactly

Yeah. Right. That's exactly what he said.

I knew I'd have to spell it out for you. Analogizing populist anger toward Wall Street (or, say, conservative anger toward the media) to antisemitism is offensive because Wall Street is not an ethnic group (unless Will means to imply that Jews control Wall Street, but even I don't think he's that stupid).

It diminishes the seriousness of actual antisemitism. This is why groups like the Anti Defamation League decry the wanton use of antisemitism analogies, like PETA's "Holocaust on Your Plate" campaign.

Maybe that's because that's not what Will's column is about, Sven. This column isn't about locating the causes of the present crisis.

Granted, it's in the form of a rhetorical question, but he says explicity that the "excessive diversion of capital into the housing stock" - i.e., the present crisis - would not have happened without "government manipulation" via Fannie and Freddie. That's stone-cold stupid. The excessive diversion was instigated by the Fed and implemented by...Wall Street.

Now, it's possible to make a broader critique that the American economic system has become overly dependent on debt. But that's not what he did.